5. Local Knowledge Accumulation

The reference table of suitable or dangerous weather conditions for the blight is also modified by the results of laboratory experiments. One laboratory result that can be controlled for temperatures and relative humidity is the condition that “a temperatures of 30°C for a certain period of time” kills the fungus. In other words, it is a disincentive for blight outbreaks.

In Sankhu, there are days when the maximum temperatures exceeds 30°C (86°F) and the leaf surface of the potato plant dries out in less than 30 minutes, and although BLITECAST-Wisdom does not specify the 30°C condition 9), the FLABS prediction method requires that days when the average daily temperatures is above 26.6°C (79°F), the cumulative value of the infection likelihood index is reset to zero. On the other hand, in terms of disease outbreaks in the low temperatures zone, the FLABS 7.2°C condition has a significant effect on the favorable index for blight disease in Sankhu.

A review of the history of epidemic forecasting provides an important decision-making tool when creating a system for forecasting the break date of the epidemic. The first forecasting began in 1938 10). In 1948, a ‘blight garden’ was set up, a field where naturally occurring blight was observed without using agricultural chemicals, and the disease status of the community was observed. From observations made in the gardens during the period 1956-1960, the original table of Table 1 was created that evaluated the conditions favorable for the occurrence of blight according to the duration of temperatures and relative humidity 8). This shows that the ability to observe lesion onset and epidemic spread in the field is most important.

There is a lesson from elder, outstanding farmer, that says, ‘Observe the crops in the fields while the dew is still wet…’ By obtaining information ‘at the time and place’, farmers can take action immediately. This kind of daily repetition becomes experiential knowledge that only he knows. It is difficult to convey his experiential knowledge to other people. However, if there are objective epidemic outbreak information such as meteorological observation values and blight garden, the experiential knowledge of individual farmers can be made into “regionally specific knowledge” and useful information in a systematic way.

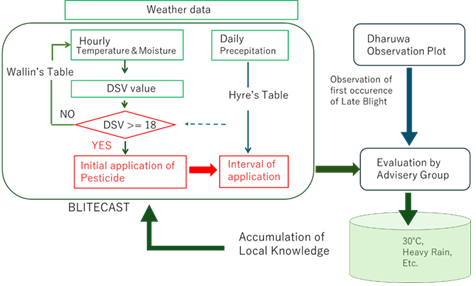

Fig.6 How to accumulate Local Knowledge against Dharuwa

RGAD has been working with a group of farmers in Sankhu to carry out meteorological observations and monitor the incidence of potato blight over the past ten years. The next step is to take a longer-term perspective and actively accumulate the experiential knowledge gained in Sankhu to create an effective system that will enable sustainable agriculture.

In the rural areas around Kathmandu, communication facilities are developed and smartphones are widely used. A web application provided by a private weather company provides free hourly weather forecasts for any location near the user’s current location. However, these weather forecasts are estimates, and they differ from actual measurements taken at the field level, and they do not provide reliable hourly data. It is important to observe the weather yourself, and the accuracy of simple weather observation measurement is also improving.

In the past, creating a local agricultural meteorological information system using a communications network required a very expensive investment for the communications infrastructure. Nowadays, it is possible to easily create a network of information linking farmers using smartphones by using the cloud. In this case, robust field servers that can automatically continue weather observations and accumulate data are essential. It is also important to set up blight observation fields that do not use agricultural chemicals at key locations and record the date of the first outbreak of blight in the region. By having farmers observe and record the growth of potatoes and the occurrence of blight at key points in the farming area, it is easy to create a blight observation system. Such an information system is not only useful for blight control, but also for daily farming work and obtaining marketing information.

Field servers installed in the field collect “on-the-spot” information, which is immediately linked to the farmer’s decision-making. The results of individual farmers’ decisions are information and empirical knowledge known only to the farmer. However, because it is backed by objective information collected by the field servers, it creates an opportunity for collaboration between farmers and agricultural extension specialists and researchers. It is nothing less than the accumulation of local knowledge to achieve sustainable agriculture in Sankhu. It also represents a new way of agricultural technology dissemination.

9) Ikeda et al. (2016) verified the 30°C condition with pest observation field data in Hokkaido, Japan.

10) See Wallin (1962) for the process of developing epidemic forecasting methods.

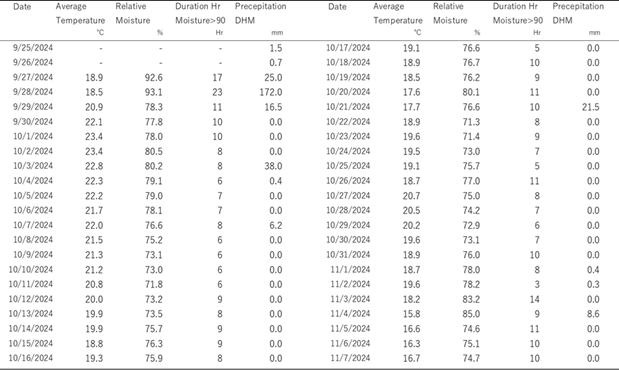

Table 3 Appendix Table Daily Weather Data in Sankhu, Summer Potato Season 2024